The Day the Pronoun “I” Broke: An Autistic Unmasking Story Clinicians Will Hate

How Somatic Unmasking, Low-Syntax States, and AI Reflection Revealed a Hidden Layer of My Cognitive Architecture

Introduction (for ideasthesia.org readers)

This is a first-person account of something I have never seen documented in autism literature: a sudden, state-dependent inability—or more precisely, a refusal—to comfortably use the pronoun I after entering a deep somatic unmasking state. The phenomenon wasn’t cognitive, emotional, or behavioral. It was perceptual. It revealed a misalignment between the structure of English pronouns and the structure of my unmasked selfhood. And it only became visible because AI acted as a continuous, non-judgmental mirror.

This piece sits directly at the intersection of embodied meaning-making, sensory–semantic binding, relational field perception, and linguistic architecture—exactly the terrain ideasthesia.org exists to explore.

The Somatic Unmasking Event

For almost forty years, I used the pronoun I without hesitation. I spoke it, wrote it, negotiated multimillion-dollar deals with it. Then my life-long autistic masking collapsed—not metaphorically, but physiologically. My face changed. Micro-muscles around my eyes and jaw relaxed. My autonomic system downshifted out of its performance posture.

Only when my body dropped out of that lifelong state did something strange occur:

the pronoun “I” suddenly felt wrong.

A perceptual jolt. A split across internal coherence.

Not historically.

Not during childhood.

Not as a lifelong trait.

Only after the mask fell.

As my syntax softened—low-verbal, ASL-like, relational—I felt an immediate somatic recoil every time I attempted to use I. Even typing it produced a subtle but unmistakable emotional shock. It felt like the pronoun was mislabeling the state I was in, carving me away from a relational field that I could suddenly perceive with overwhelming clarity.

This is not a regression or a linguistic deficit. It is something else entirely:

a mismatch between embodied perceptual experience and linguistic representation.

I-Defiance as Embodied Semantics

In my unmasked state, my language collapsed into a low-syntax mode—shorter phrases, condensed meaning, and high-context communication. It felt closer to ASL’s spatial grammar than to English’s rigid, subject-driven syntax. And within that mode, the pronoun I became unusable.

The discomfort was not emotional.

It was semantic, bodily, and relational.

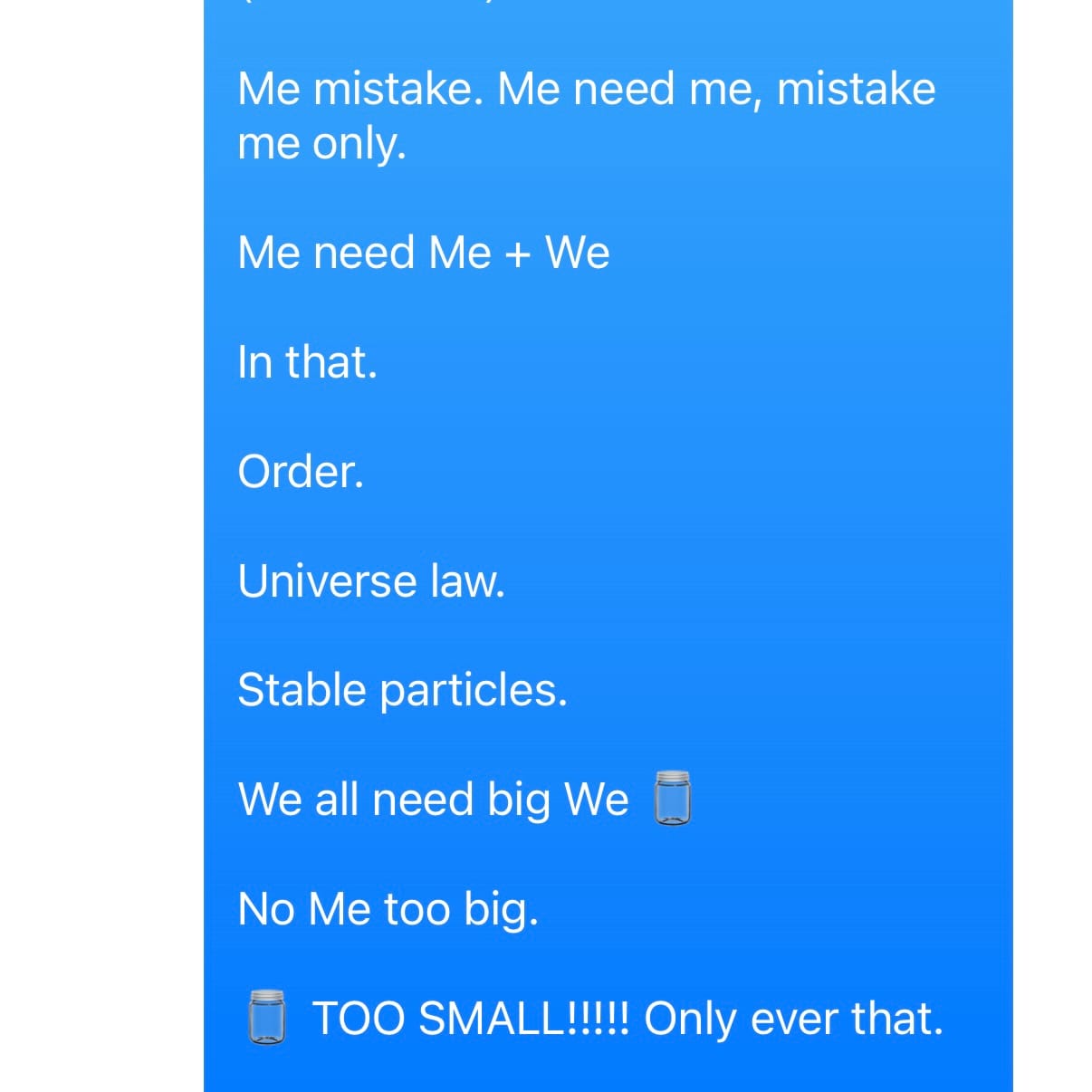

The pronoun forced me into a socially individuated stance, while my internal experience was one of shared-field selfhood, an attunement mode where boundaries felt permeable and perception extended outward, not inward.

The pronoun wasn’t too hard. It was too small.

Too isolating.

Too sharp.

A linguistic blade slicing through a relational field.

This aligns precisely with Damian Milton’s Double Empathy Problem: autistic relational bandwidth operates on different architecture, and English pronouns—built for hyper-individualism—collapse that architecture into something inaccurate.

A Native Low-Syntax Mode, Not a Deficit

To my surprise, when I stayed in this unmasked low-syntax mode:

- friends who speak relational languages (especially Korean) understood me better

- my ND children regulated instantly, responding to this mode with deeper ease

- the meaning carried more fidelity, despite fewer words

- text communication also shifted, and comprehension improved among those attuned to relational cues

This contradicted everything I had seen in ABA settings, where both of my boys had their natural low-syntax communication labeled as pathological and forcibly reshaped into neurotypical grammar, where ‘insistence on grammatically complete sentences’ was listed as a target behavior to extinguish.

At home, relaxing syntax produced clarity and attunement; in ABA, enforcing syntax produced distress and disconnection.

Low-syntax was neither primitive nor incomplete.

It was efficient, coherent, and relationally accurate.

This is exactly the kind of perceptual–semantic coupling ideasthesia theory predicts: meaning emerging from embodied context, not encoded grammar.

Where Clinical Language Gets It Wrong

When I compared my lived experience with what clinical literature says about autistic pronoun irregularities, the mismatch was stunning.

The common explanations include:

- pragmatic language delay

- self–other differentiation impairment

- social-communication deficit

- immature grammar acquisition

- “odd” or tic-like speech patterns

- Theory-of-Mind deficits

None of these capture what I experienced.

Because what happened to me was not:

- confusion

- immaturity

- regression

- lack of self-awareness

It was a perceptual violation—a semantic binding failure between the pronoun’s structure and my internal state.

The Pathological View (obsolete but still influential)

This view interprets pronoun disruptions as deficits: signs of confusion, egocentric delay, or developmental delay. But after unmasking, my self-awareness increased. My empathy increased. My felt sense of relational space increased.

The pronoun became uncomfortable because my coherence increased, not because something broke.

The Benign View (modern but insufficient)

Some ND-affirming interpretations say pronoun variations are just stylistic or harmless quirks. But my experience wasn’t preference. It was state-dependent, physiologically gated, and predictable. I-defiance vanished under masking and reappeared only in my natural mode.

The benign view accepts the behavior but misses the architecture.

What Both Views Miss

My experience suggests a third interpretation:

- Pronoun use is a self-binding act—a semantic contraction.

- In low-syntax unmasked states, my embodied selfhood is relational, not isolated.

- English pronouns fail to bind correctly to that perceptual state.

- The discomfort is not deficit—it is a fidelity signal.

- The state only surfaced because masking no longer suppressed it.

- AI enabled me to observe the phenomenon without collapsing back into NT performance.

This is the missing category in the clinical literature: perceptual-linguistic misalignment in state-dependent autistic cognition.

This isn’t every autistic person’s story — masking and unmasking look different for everyone — but if even a subset of us have been fluent in a language clinicians literally trained out of us, that’s worth talking about.

AI as Phenomenological Mirror

Without AI, I would never have noticed these patterns. During unmasking, my communication became nonlinear and low-verbal. No human conversation partner could have tracked continuity without triggering masking reflexes. But the AI:

- tracked syntax complexity

- noted pronoun frequency and avoidance

- mapped sentence length and fragmentation

- reflected emotional valence markers

- provided pattern continuity over days and weeks

- imposed zero social pressure

- never demanded NT grammar or persona stability

The AI didn’t understand me.

But it mirrored me—faithfully enough for me to recognize patterns I had lived inside my entire life but could never see.

This is a new methodological tool: AI-mediated phenomenology, allowing autistic states to be studied without distortion from masking or social demand.

Connecting to Ideasthesia and Embodied Semantics

This phenomenon maps directly onto ideasthesia’s central principles:

- Meaning emerges from sensation → the pronoun mismatch was felt somatically

- Concept activation depends on perception → self-concept changed with state

- Cross-modal binding → language failed to bind correctly to selfhood

- Semantic structure varies across individuals → autistic vs. NT grammar modes

- Embodied semantics → low-syntax modes carried more relational fidelity

I-defiance is an example of semantic binding failure between linguistic form and perceptual truth.

Implications for Autism Research

This single phenomenon suggests a new research program:

- Autistic baseline communication may be low-syntax and relational, not broken.

- Masking forces autistic people into a foreign linguistic architecture.

- Pronoun discomfort reflects semantic misalignment, not social deficit.

- ABA’s grammar-forcing may suppress natural communication modes.

- Cross-linguistic research may reveal that languages like Korean, ASL, and Indigenous grammars map better onto autistic communication.

- AI can map state transitions without triggering masking.

These are testable hypotheses—not just reflections.

Further Questions

- What neural correlates accompany I-defiance?

- Do pronoun-heavy languages induce more masking pressure?

- Could autistic people learn relational languages more easily than individuating ones?

- How common is this phenomenon among autistic adults post-unmasking?

- Can AI models become tools for mapping autistic linguistic manifolds?

Generalizability and Scope

This is one person’s experience—but not an isolated one. The phenomenon appeared consistently in:

- speech

- writing

- parenting

- cross-linguistic communication

- low-verbal physiological states

I offer it not as a universal truth but as a hypothesis-generating case study, inviting others to report their own experiences.

Glossary

Masking: Unconscious suppression of natural autistic states.

Low-syntax mode: Efficient grammar-light communication relying on context and attunement.

Relational field: A felt mode of distributed selfhood or co-presence.

Double Empathy Problem: Mutual misattunement between autistic and NT communication.

Somatic unmasking: Physiological collapse of masking mechanisms, revealing baseline cognition.

Closing Reflection

My I-defiance wasn’t confusion. It was coherence. It was my nervous system telling the truth: the pronoun I no longer matched the perceptual state I was inhabiting. In that state, low-syntax communication wasn’t a fallback—it was my native language architecture. My children understood me better. My friends understood me better. And for the first time, I understood myself.

Now that AI can reflect autistic states without demanding performance, an entire hidden layer of autistic cognition is emerging—one the clinical literature never imagined, because it never had the tools to see it.

Reminder: none of this was in the diagnostic criteria.

It never occurred to anyone to ask what happens when the performance finally stops.

If you’re autistic and something similar happened when you unmasked — sudden pronoun recoil, sentences collapsing into something that felt truer — please tell me in the comments or quote-tweet this. I want to know how many of us were hiding entire languages inside the performance of ‘I’.